Bureaucracy is often regarded as the backbone of the governance structure of a country. This large state apparatus plays a critical role in policy formulation, implementation and the delivery of public service in India. India’s bureaucracy has been the backbone of governance since independence (S. Ganesan, 2024).

The Indian bureaucracy holds the title of being one of the largest and most complex administrative structures in the world (ISPP, n.d.). It is a system that is rooted in colonial legacy and has played a critical role in events that transpired post-independence, such as nation-building, governance and policy implementation. However, as the world around continues to evolve with India’s evolving as well, characterised by globalisation, advancements in technology and shifting socio-economic priorities, the need for this very system to undergo reforms has become more pressing than ever.

History of Indian Bureaucracy

The administrative machinery in India was designed primarily for maintaining law and order and implementing government policies. This “steel frame” of governance has evolved significantly, spanning centuries together. The origins of India’s bureaucracy can be traced to ancient India, with structured administrative systems finding their roots during the Maurya and Gupta empires. A seminal work in this regard is Kautilya’s Arthashastra, which details statecraft and administration during his time, emphasising hierarchical governance and centralised control (Sharma, 2005). The Mughal Empire further refined the administrative process by introducing their own revenue collection system and systems of regional governance through mansabdari (Ali, 1975).

These developments were followed by the instituionalisation of bureaucracy in India during the British colonial period. Initially, the territories were administered by the East India Company. However, the Government of India Act, 1858 transferred authority to the British Crown. This period also saw the establishment of the Indian Civil Service (ICS), designed primarily to ensure efficient administration. Eventually, the ICS became the backbone of colonial governance, implementing policies that helped the British consolidate power, while functioning at a distance from the local populace.

India’s independence in 1947 paved the way for India to inherit this bureaucratic framework. The All-India Services, which constitute the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Police Service (IPS), and Indian Forest Service (IFS), were instituted ensure a standard form of governance across states while keeping the federal structure intact (Chakrabarty & Bhattacharya, 2005). While the bureaucracy has been lauded for its role in maintaining stability and facilitating the necessary development in the socio-economic sphere, the system has also drawn criticisms for being overly rigid. Several scholars, like B.B Misra (1977) have highlighted issues of inefficiency and the persistence of colonial attitudes within the service.

Challenges Facing the Indian Bureaucracy

There have been several challenges staring the Indian Bureaucratic machinery, highlighted by multiple scholars across a plethora of academic work, published throughout India’s post-independent history. Some of these have proven to be structural hurdles for the state apparatus, making it difficult to implement policies and changes. Some of these include, but are not limited to:

The Indian Administrative Service and other civil services alike were modeled along the British system. Such a system emphasised on hierarchy, procedure and control rather than innovation and problem-solving. This colonial emphasis on compliance and centralisation persists, often bypassing adaptive decision-making and innovation (Maheshwari, 2005). This rigidity is often visible in the obsolete recruitment procedure, promotion systems and excessive procedural formalism which stifle its adaptability to the contemporary socio-economic challenges (Misra, 2011). Despite several initiatives like e-governance and lateral entry, entrenched resistance to reform limits their transformation.

Red-tape is a widespread feature of government bureaucracies. It finds its roots from the colonial administration, manifesting itself in lengthy approval processes, redundant paperwork and an emphasis on hierarchical decision-making (Singh, 2018). For instance, certain infrastructure projects face years of delays due to clearances required at multi-level clearances from various government departments. The health sector, for example, suffers from bureaucratic bottlenecks resulting in shortages during emergencies. These inefficiencies and delays not only slow down development process but also discourage private players from entering the sector, by increasing the cost of doing businesses.

As times evolve and India continues to grow, it is necessary to transform this key pillar of India’s governance architecture. The training modules for civil servants are seen as being outdated, failing to address contemporary challenges. In this regard, there is a need for continuous learning and upskilling in areas such as policy formulation, digital governance, and crisis management to ensure bureaucratic readiness and effectivity in a rapidly evolving landscape.

Another principal concern of this apparatus is the lack of accountability. The lack of accountability affects the delivery of public services and governance outcomes. As stated in the work, Accountability Mechanisms in Indian Bureaucracy, the deficit stems from opaque systems of evaluation, weak enforcement mechanism and limited public oversight. The work further goes on to state that bureaucrats often operate with significant autonomy but without a sufficient system of checks and balances. The bureaucracy also lacks a robust performance appraisal system system which results in promotions being based on tenure, rather than merit. As stated in another work, Politicization of Indian Bureaucracy, the author notes that accountability is further diluted by overlapping jurisdictions, where multiple agencies share responsibilities without clear lines of accountability (Rai, 2019).

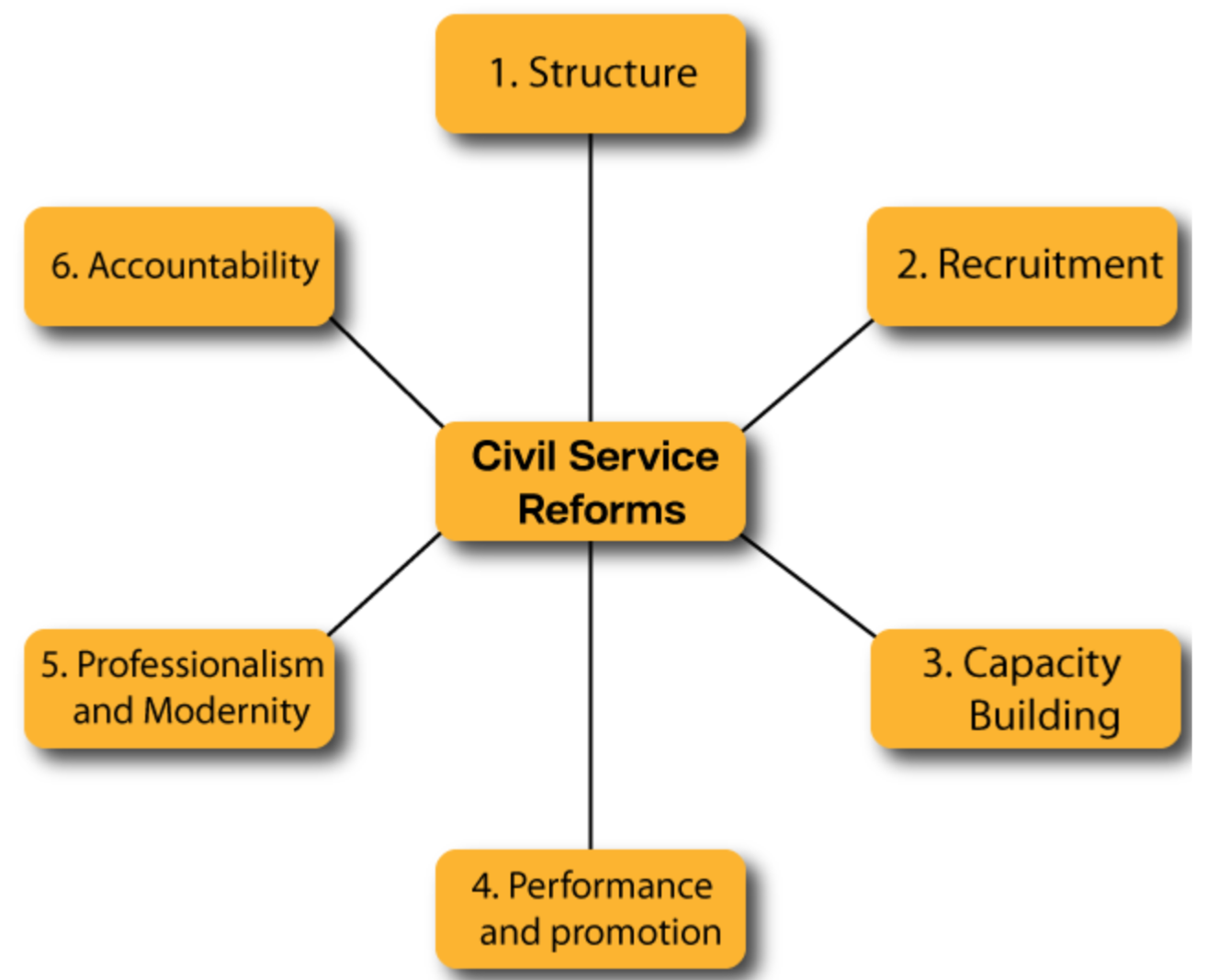

Reform Measures to the Challenges

The reduction of red tapism in Indian bureaucracy requires systemic reforms aimed at simplifying procedures and enhancing transparency. One solution in this regard is E-governance, which aims at streamlining processes by minimising paperwork, digitisation and expediting approvals (MeitY, 2019). Certain platforms like the Government e-Marketplace (GeM) have reduced procurement delays and improved efficiency (World Bank, 2020). As highlighted by the Second Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC, 2008), another approach involves the rationalisation of rules to eliminate redundant regulations. Integrating citizen feedback mechanisms and adopting performance-based evaluations can ensure there are no delays (Sharma, 2021).

Certain training initiatives like Mission Karmayogi promote adaptive skills among bureaucrats, equipping them to implement reforms effectively. Further, to foster decentralised decision making, local governance bodies can be empowered under the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments, reducing bottlenecks and hurdles significantly (Jha, 2014).

Lateral entry into the bureaucracy, another area of reform, involves recruiting individuals from outside the conventional government service cadres to fill mid and senior level positions. The concept of lateral entry is a historical oversight, recommended initially by the Second Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC) established in 2005 by the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance. The ARC, chaired by Veerappa Moily batted for lateral entry into the services to fill roles requiring specialised knowledge, unavailable in the traditional recruitment practices. Lateral entry into bureaucracy was formally introduced during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s tenure, with the first set of vacancies announced in 2018.

In this aspect, it is worth commending the MEA’s efforts in encouraging outside talent for jobs in the Ministry. Around 12 such officials were hired as subject experts attached with the policy planning and research division of the External Affairs Ministry. However, they don’t have decision making or administrative powers. In this case, it is crucial for the MEA as well as other ministries and the bureaucracy to continue venturing on this initiative of encouraging lateral entry from the private sector as well as from think tanks across India.

The 73rd and 74th Amendments to Indian Constitution have empowered local bodies, promoting decentralised decision-making and improved public service delivery (Jha, 2014). By decentralising the decision-making apparatus in the Panchayati Raj Institutions and Urban Local Bodies, the gap between governance and grassroots stakeholders can be bridged. This template has the potential to mitigate bureaucratic hurdles and inefficiencies by fostering participatory governance, ensuring quicker resolution of local issues and reducing dependency on the higher rungs of administration (Chaudhari, 2018).

The Performance Monitoring and Evaluation System has been a noteworthy initiative in this regard, introduced by the Government in 2009. This aims at fostering greater accountability in bureaucracy as it established a Results-Framework Document (RFD) for each department, outlining measurable goals and performance indicators (Kumar, 2012). The PMES enables periodic assessments to identify gaps and ensure transparency in operations. Despite the measure being an effective measure to counter the challenges faced, its success depends on consistent policy implementation and robust feedback loops to refine the performance benchmarks (Ghosh, 2017).

Conclusion

Bureaucratic reforms in India are essential, as the country seeks to rise higher in its stature in the world. While this would require India to have a robust and strong economy, it also requires the country to device and have a permanent executive which can aid and advice in efficient policy making to cater to this ambition of the country. Many issues such as the Ease of Doing business in the country can also be achieved by efficiently tailoring and nurturing the bureaucracy to serve an India which desires to be world power. The Indian bureaucracy will have to embrace innovation and foster creativity in the times to come.

Sources:

- Indian School of Public Policy. (2025, March 28). Reforms for the Indian bureaucracy in the 21st century. https://www.ispp.org.in/reforms-for-the-indian-bureaucracy-in-the-21st-century/

- Kumar, N. (2012). Performance Evaluation in Indian Bureaucracy. International Journal of Administrative Sciences, 18(1), 35-50.

Ghosh, S. (2017). Accountability Mechanisms in Indian Bureaucracy. New Delhi: Sage Publications. - Jha, P. (2014). Decentralization and Local Governance in India. Indian Journal of Political Science, 75(4), 45-63.

- Chaudhuri, S. (2018). Fiscal Federalism and Local Governance in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 53(21), 47-54.

- Mathew, G. (2019). Decentralized Planning in Kerala: A Model for the Nation. Governance Studies, 14(1), 67-81.

- ARC. (2008). Report of the Second Administrative Reforms Commission. Government of India.

- MeitY. (2019). Digital India: Transforming Governance. Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Government of India.

- Sharma, R. (2021). Mission Karmayogi and Civil Service Capacity Building. Governance Insights, 9(4), 56-72.

- World Bank. (2020). Improving Public Procurement through Technology. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Kumar, N. (2012). Performance Evaluation in Indian Bureaucracy. International Journal of Administrative Sciences, 18(1), 35-50.

- Rai, S. (2019). Politicization of Indian Bureaucracy. Journal of Democratic Studies, 14(2), 89-104.

- Second ARC Report (2008). Refurbishing Personnel Administration.

Misra, B. B. (2011). Government and Bureaucracy in India. - Subramanian, G. (2024, November 23). Reinventing India's bureaucracy. PGurus. https://www.pgurus.com/reinventing-indias-bureaucracy/